Gui Ao’s shadow was long as he returned to the Fengs’ House of Infinite Dawn, passing between murmurs of him and his brother’s thrilling show from those who kept watch to see the shunned side of Fanxing’s most curious lover’s spat retreat. The sun was just beginning to peek over the buildings, illuminating the sky in a beautiful gradient of pastel fire. Ao looked up and briefly observed the stars slowly fading, hoping Lin’ai would find the answers that he needed on the mountain. He hoped that the quickly swelling day would make his travels safe, that he’d return to his older brother as healthy as he left.

The dust of his still sleepy footsteps quickly dissipated behind him. Ao pulled the abused mess of his shirt back up on his shoulder as he approached the Feng’s ostentatious entry gates.

“If this is about Quan, he’s a liar,” he suddenly announced, wavy hair swept behind an ear. “Besides, I’m a great driver. You should know that, you’re the one that taught me.”

Consistency was the only thing keeping Ao’s words from being spoken to shadow and air; Ban, first husband of the Feng patriarch, was always the first soul up before the break of day. He’d been awake when Lin’ai crept through the compound to make his quiet escape and, so, he was present when Ao completed his dramatic walk of shame.

Despite all the finery lavished upon him by his husband, Ban was an austere man with little interest in his husband’s riches. He embodied the lessons of his upbringing in the forests surrounding Fanxing. He took great pleasure in simple moments and sought daily reprieve from the ostentatious show of the house he had come to live in.

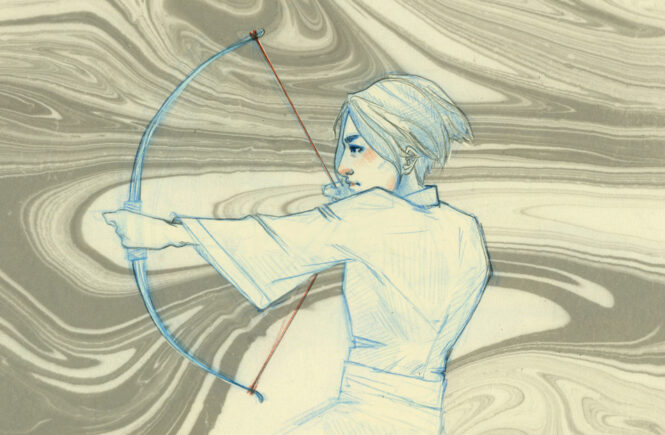

Already dressed, the Feng clan’s swordmaster tossed the newly returned Gui boy a bow, a gift hand carved and strung in red. Over his broad shoulder were two quivers. When Ban passed Ao, he only briefly paused as he surveyed the waking morning, judged the day by the way the sun threatened to break like a yolk across the road.

“Ten minutes,” the older man said. “I’ll tack Potato.”

“Oh—” Ao caught the bow, turning it over and over in his hand before looking back to that skilled fighter. “‘Kay.” He shuffled forward then, feet not fully lifted from the ground as he tried to keep his open shoes on, fingers of his free hand clutching a leg of his loose-fitting pants.

Seven minutes later, the eldest Gui boy was jogging up to the Feng clan’s stables, a gaudy building whose corners were edged with gold, whose windows were draped in red. His clothes were freshly laundered but they still showed their wear—spending most of their time on the road meant that there was little opportunity to buy new items, and the brothers maintained a consistently conservative budget to be certain that each time they came back to Fanxing they weren’t going to be thrown into debtor’s prison for not paying on the loan taken out with their uncle.

When Ao found Ban, he was slightly out of breath. Perhaps he was worried that he wouldn’t make the window of time he’d been given.

“Okay, okay,” he said, words staggered in a series of gentle huffs. The bow remained in his grasp. “Where are we going?”

Tugging the final straps taut across Potato’s belly, the elder swordsman focused on his task before he even considered the question. Fastening the second quiver full of hand fletched arrows at the horse’s haunch, Ban allowed a long moment of quiet to pass before he drew himself away from Ao’s horse. He gently patted Potato on the nose before moving to adjust the reins on his own horse, Kite.

“Hunting.” Ban was generally sparse with his words. He made himself known through action; found listening far more useful than speaking. Looking up, the older man glanced from boy to bow and back again, dark, evaluating eyes settling on Ao’s face. “Do you like it?”

“Yeah, it’s nice.” Ao stepped up to take Potato, guiding the mare out into the daylight. “Whoever made it did a really good job.”

Aligning the horse with a mounting block, the boy stepped up and easily slung his leg over her back, settling behind the pommel of his saddle. He let his stirrups dangle footless for the time being, content to hang his feet leisurely at the horse’s side.

“What’re we hunting?” Ao called back to Ban, steering Potato into a large circle around the swordsman, predator gaze present even when he wasn’t actively trying to present a threat. “Why are we hunting? You can just pay someone to do this for you.”

“The food here is too rich to eat without working for the meat,” Ban replied, leading Kite out of the stable before he mounted, sitting tall and proud as a general upon that black stallion spattered with grey and white stars. “We hunt what we find: deer, pheasant…” Laughing low to himself as he urged his horse forward and to the right, Ban tossed his last comment over his shoulder. “…monsters.”

The reckless youth followed behind the Feng husband, nudging Potato into a short trot to catch up the few steps they’d been left behind. “Did you get Lin’ai something too?”

“I’m still working on it.” Ban looked to the side to gage the youth’s proximity before he looked ahead. “It takes time to carve a bow of good quality; to consider its weight and balance in respect to the archer.”

“Oh, did you make this then?” Ao dropped Potato’s reins, lifting the bow and taking an archer’s posture, sharp elbow jutting from his side as he looked down his long arm at a merchant in his sightline’s dead end. The man yelped and scurried into the shadows, terrorized by that boy who didn’t even have an arrow in his clutches. His horse, meanwhile, walked freely. The Gui boys were tightly bonded to their animals, cared for them like the family they were, trusted them more than humans.

“I did.” From the corner of his eye, Ban watched the Gui boy test out the bow, a shadow of a smirk forming at the corner of his lips, hidden by his beard. “I fletched your arrows, too. Your aim is true enough that you are spare with your ammunition—or you are spare with your ammunition so you only take sure shots. I trust you’ll care for them.”

“I’ll use them wisely.” That was the extent of the care Ao was willing to offer, bargainer’s tongue firm despite the ease with which his words came. He stashed the bow and picked up Potato’s reins again. His dark eyes shifted to watch Ban, naturally narrowed, chin turned aside. “Are you going to make Lin and I train with the rest of the team before challenging for the Millipede?”

“Feng Quan does not require the Millipede,” Ban said simply. There were a great many things Feng Quan did not require; Ban always found the blonde boy greedy for things others needed and repulsed by all things he was lacking. A lifetime of tutelage had done nothing to fix this: Feng Quan was fundamentally flawed, spoilt before anyone could salvage him. “The terms of your contract must favor you. What you do is your own choice.”

“Okay.” The Gui boy nodded, content to leave the topic of contracts and Quan as it stood, although he doubted the swordsman would press him for further details of the goings on between him and his cousin. Ban was different from the rest of the Feng clan, he never treated the pair of Guis like they were a burden or a monetary investment. Since he was a teen, old enough to recognize wickedness in the world and too young to do anything about it, Ao respected Ban for his humanity in that house full of monsters. He didn’t understand it—but he respected him all the same. The youth turned away from his elder to watch the road.

“I hope we get pheasant,” he said, grin growing bold like the morning.

“If we find pheasant, we’ll have to shoot two: one to roast over a fire before we head home and one to bring back for Lin’ai,” the swordsman said. Ever since he was a child, Lin’ai was more fond of birds and fish when abundance gave him options. Livestock reminded him of horses and all horses reminded Lin of Turnip.

They continued out of the city and into the chittering arms of the forest, sheltering under tall bamboo canopies before the sun could beat too cruelly upon their backs. They crossed a stream before Ban led them off the main road, deciding on an overgrown hunting path he hadn’t trespassed since marrying Youzui.

“How’s your mother?” The words were casual and abrupt all at once. “Have you visited since your return?”

Ao’s spine straightened despite the nonchalance coating his tongue. “No, we haven’t seen her. Quan wrapped us up in his dumb shit before we had a chance to. Maybe before the challenge. Maybe after. If you want to know how she is, why don’t you ask her?” Dark eyes met the swordsman as Ao urged Potato past him on the narrowing path, through an overgrowth of twigs reaching out like the skeletal hands of souls long gone. For most men, it was a preposterous suggestion. That boy’s mother—the murderess black widow of the condemned Gui line, venomous swordmistress of the Zhenxi sisterhood—was feared by anyone who had a lick of common sense.

“Because I’ll die.” Ban’s response was matter-of-fact, a statement of the obvious. As far as Ao knew, Ban was no different than any other man: a target defenseless to Gui Naohe’s crimson web. “It is important to keep close to your roots, honour the tree that crafted you.”

“Some of my roots were rotten, you know,” Ao replied, subtly solemn in the midst of his blood-hungry mischief-making. “Even though they were severed, sometimes I wonder if that rot had a chance to spread, turn mine or Lin’s trunk into a grotesque and misshapen egoist like the rest of the Fengs. I don’t want to be like them. I don’t want to keep close to or honor these roots, despite my obligation.”

After a moment, the youth smiled again, sharp teeth turned back on his companion. “No offense.”

With a hum, Ban rubbed at his jaw. Somewhere beyond that impassive brow, there was conflict, a roil deep beneath the surface of an eerily silent lake. “Ah, maybe it’s time.”

“Should I run now?” The Gui boy asked, prepared for some consequence to his impertinence.

Ban was always a direct man, he had little use for subterfuge or diversion. Though the swordsman had his secrets, revelations rarely came with leadup: just information meted out in neat, clearly worded parcels.

“Feng Huacai is not your father,” Ban informed the boy with the same gravity one might use to comment on the weather. “You will never have to worry about the roots rotting the tree.”

“What?” Ao pulled Potato to a halt, turning her body to block the way up the isolated path. He stared hard at the older fighter, distrust an expression so easily summoned when one lived a life of uncertainty. “What is this, some sort of trap to make sure Lin and I don’t get any inheritance when our uncle passes or something? To enforce a higher interest rate now that we’re of age, unbound by the kindness shared between blood?”

Still, behind those narrow eyes shaped by all that was wrong in the world, that mouth which questioned futures and finances, was a boy who’d just been unseated from his assumed place in the world—a boy who now questioned who he was, where he came from, why the blood of a man who wasn’t his father stained his poison-soaked hands.

“How do you know this?” Ao questioned further. “Why are you saying this now?”

“I’ll tell you what I can,” the elder replied, keeping his eyes ahead as he bid Kite off the path and past Ao’s obstruction. “But it is a long story better shared over a fire and a pheasant.”

After a brief hunt, Kite and Potato grazed peacefully near a pristine creek lined with black and blue river rocks. Ban had built a fire and a makeshift spit in the sprawl where stone gave way to grass, shielded from the midmorning sun by the reaching arms of the wood. A freshly cleaned pheasant was roasting between the men. Ban watched the horses as he took a drink from his water skin, tossing it to Ao before he leaned back against the exposed roots of an old gnarled tree.

“How much do you know about the Gui clan, the tribe your mother comes from?” Ban asked the young man.

Ao shrugged, idly holding the canteen between his knees for the time being. “Mom’s been slowly opening up when we are allowed more than just a short time to be with her. She’s busy, you know? Sometimes it feels like there’s only enough time to tell her that I love her before we have to leave again.” The youth adjusted, leaning forward with his elbows propped upon his legs. He sat on a boulder, a lonely granite tooth protruding from the verdant flesh of the earth. His cheeks were dusted with remnants of the trail, fine ground dirt kicked up by the excitement of a chase. “Fath—er, Feng Huacai was strict with us growing up. He didn’t like our laughter, didn’t let her tell us stories.”

Ban frowned at the comment even though he knew Feng Huacai’s temperament well, knew the way his husband’s younger brother treated the boys when they were small. Regardless, he continued, straightening his spine as he watched the flames. “Your father’s name was Ying Jianyu. Back before the war against Zao Beiguan, the forests outside of Fanxing were controlled by an alliance of many tribes, led by the Ying and the Gui. We were different from the people of Fanxing, believed that artifacts weren’t meant to be controlled by individual men. We believed in the common good, the riches of the group; we were opposed to the quest for individual power that built Fanxing, that built the Arena.”

“We?” Ao’s eyebrows bunched, curiosity a direct product of his rapt attention. “So which were you, Gui or Ying?”

“Ying,” Ban confessed, leaning forward to give the pheasant a turn. “Your mother was in love with Ying Jianyu long before the war but her father arranged her to marry Feng Huacai. Our people fell upon famine because of Zao’s resource hoarding. The Feng clan offered food stores in exchange for a secure route through the forest and the treaty was sealed by marriage. We banded with the upstarts to preserve our way of life but our trust was betrayed by the very clan that brought us into the fray.”

“No surprises there—given the opportunity, a Feng’s left hand would betray the right.” Though he spared a glance toward the bird, Ao’s gaze quickly returned to the swordsman. “The betrayal was severe enough to wipe out all mention of these tribes then? Or were the tribes too distanced from Fanxing that no one really knew about them or cared?”

“Perhaps it was both.” Shaking his head, Ban leaned back and looked at Ao. His gaze was softer now than it ever was in the Feng household, misty with an affection never openly stated. “In order to clear all routes through the forest, the Feng clan laid plans to brand our people traitors and succeeded in wiping out huge swathes of our warriors. On the eve of the Battle of the Black Garden, before Tian Yunyong took the throne from Zao Beiguan, the brothers Feng sent a bird that launched our attack at the wrong location, where Zao’s army waited in ambush. They wiped out an entire people so they could take our treasures, rip the artifacts from our sacred totems and claim them as their own; they swept in when both armies had been whittled down, taking credit for the victory that our tribes won, saying they had destroyed a blended army—that Ying and Gui were there to rally behind Zao.” Hurt cast its long shadow over the swordsman’s chiseled features. His clenched fists belied his long held rage, tendons taut as a bowstring.

Ao was not entirely unlike the man who sat before him. Fury was an emotion that always simmered beneath the Gui boy’s exterior, it was a feeling he was committed to holding onto so he wouldn’t forget all the hardships that made him. Now it bubbled to the surface, visible in the way the youth dipped his chin, the manner in which he exhaled: careful and concurrently hot, full of venom burning like the blood coursing through his very heart. He searched the ground for a solution his mind was already screaming. For all the possibilities of happiness that had been taken away from him, for all the wretched times suffocating a world of happier moments, Gui Ao silently vowed that he would wring his revenge from the crimson necks of the pigs that took his life and family away from him.

He inhaled deep and looked back up to Ban. “How well did you know my father? What were you to him? Would you tell me about him?”

After a pause to recollect his calm and composure, to slay any quaver in his commanding voice, Ban responded: “I know your father well. I fought alongside him my whole life; I experienced the same hardships; I shared the same victories; I mourned the same sorrows. Ying Ao, your father is still alive. I promised your mother I would keep you and your brother safe while I rooted out evidence of the Feng’s treachery—so your father will be able to return to you without the brand of a traitor.”

“Where is he hiding then?” Ao sat up in protest, a youth tempted by all the things he never had held just out of his grasp. “Why is he hiding from me? Lin and I spend most of our time outside of Fanxing, where prying eyes are only concerned with the contents of our cargo. Why can’t I see him? Why doesn’t he trust me?”

“The last of our tribes hides deep in the forest, behind a veil of concealing totems. You cannot find your way past them, at least not yet, but please believe me when I say your father is so proud of you. He trusts you and loves you, even as he’s watched you grow from afar; he simply fears for your safety. They’re always watching. When you take your cargo into the deepest parts of the kingdom there are eyes. Even here we are only free to speak because of the remnants of wartime scrying totems.” Looking up, Ban nodded toward a trio of carved pillars, nearly completely overtaken by kudzu. “Ao: the Feng brothers destroyed an entire culture. What would Youzui do to the last Yings? What would he do if he knew who you really were? He’s had his suspicions since his brother’s death. Given a chance to try again, aware of this path’s course, your father would have wrenched you away from Fanxing’s world. He will absolutely tell you himself how sorry he is when you finally meet.” The secrets ached in Ban’s chest but he knew this pain was necessary; they’d worked too long to uncover irrefutable evidence of the Feng clan’s wrongdoing and now, Ao would bring the final piece into play.

Rising, Ban made his way over to Kite and retrieved a sheaf of old papers rolled in leather. He returned to the boy’s side and held them out to Ao. “These correspondences will clear your father’s name and destroy the Feng patriarch. They are letters between Zao Beiguan, the general who led the ambush, and Feng Youzui. Take them to your mother, Ying Ao.”

Unwilling to show the sort of emotion that blossomed from fury—the breakdown, the sadness—Ao snatched the roll from Ban and stood. He tucked the stash under his arm as he hastily walked back to Potato then slung his gangly limbs over the mare’s back. Ao climbed atop the saddle straddling her spine; he looked to Ban once more before he pressed the horse forward with his heels, back down the path they followed.

Gui Ao was hard headed when it came to being vulnerable, too proud to let anyone but Lin’ai see the full range of his feelings.